What Is ChatGPT Doing … and Why Does It Work?

Complete illustrated analysis with expandable commentary on every paragraph

The Complete Illustrated Essay

All original images from Wolfram's essay with expandable commentary on every paragraph

It's Just Adding One Word at a Time

The Core Mechanism

This single sentence captures ChatGPT's entire purpose: produce reasonable continuations. Not "understand," not "think"—simply continue text in a statistically plausible way based on patterns from training data.

Important Distinction

"Reasonable" = statistically likely based on what humans have written. This is fundamentally different from human intentional writing, yet produces remarkably similar outputs.

The Mental Model

This simplified mental model helps build intuition. Imagine literally counting what follows this phrase across all text ever written. That's not exactly how ChatGPT works, but it's the right intuition for understanding probability-based generation.

"Match in Meaning"

This hints at embeddings—numerical representations where semantically similar text has similar numbers. ChatGPT doesn't do literal string matching but operates in a "meaning space."

The Output

For any context, ChatGPT outputs ~50,000 probabilities (one per token in vocabulary). These sum to 1.0, forming a complete probability distribution.

The Iterative Process

This reveals the autoregressive nature: each word depends only on previous words. There's no "planning ahead" or "thinking about the whole essay"—just repeated next-word prediction.

Why It's Remarkable

This simple loop produces coherent essays, code, poetry, and more. Complexity emerges from 175 billion parameters, not sophisticated reasoning.

The Selection Problem

Given probabilities, how do we choose? The naive answer (always pick highest) turns out wrong. "Voodoo" signals this solution lacks rigorous theoretical justification—it works empirically.

The Creativity Paradox

Counterintuitively, adding randomness makes text better. This introduces variety, surprise, and the appearance of creativity.

The Balance

Too deterministic = boring/repetitive

Too random = nonsensical

Sweet spot = "creative" and coherent

Temperature Explained

- T=0: Always pick highest probability (deterministic)

- T=0.8: Slight randomness, good for essays

- T=1: Sample directly from distribution

- T>1: More random, more "creative"

Why 0.8?

Empirically determined—it "works." Different tasks may need different temperatures (code often uses lower).

Where Do the Probabilities Come From?

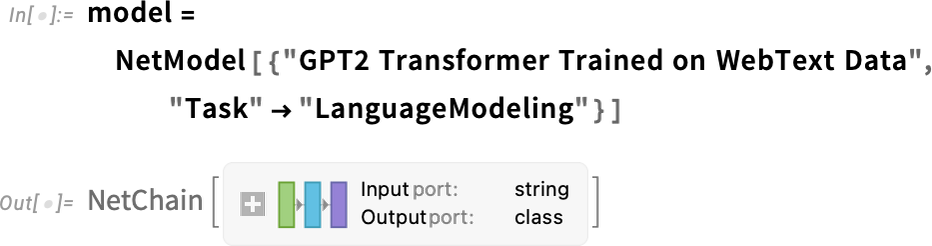

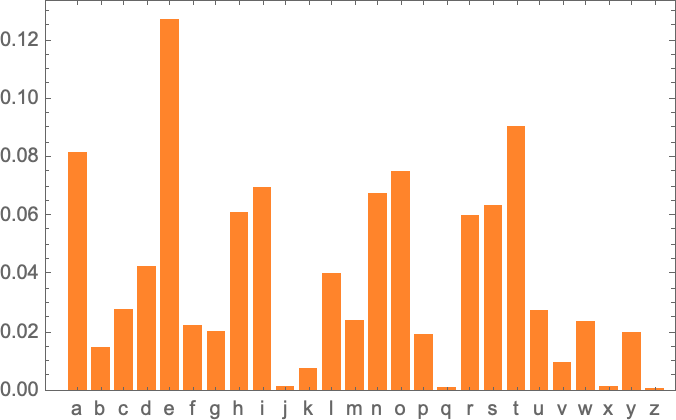

Pedagogical Strategy

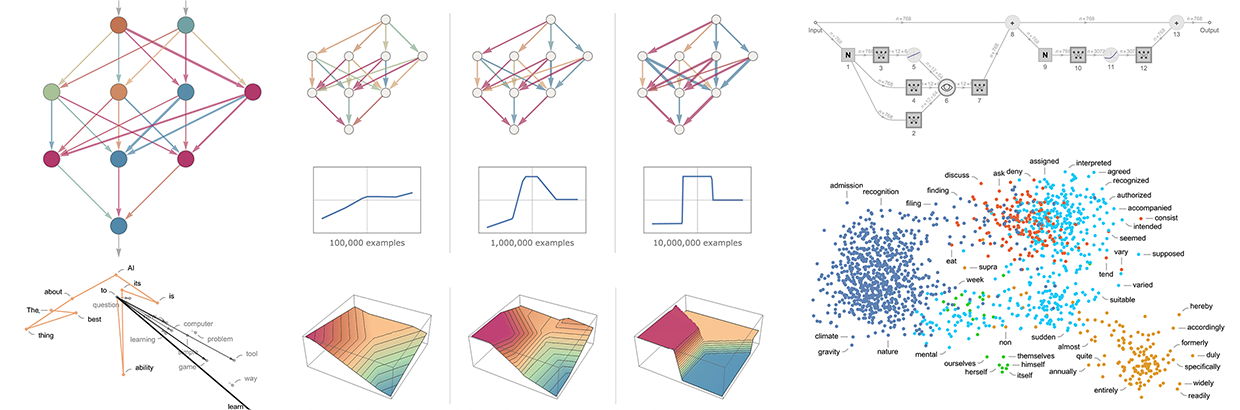

Wolfram starts with letters (26 options) instead of words (~50,000 tokens) to build intuition. The principles transfer directly but are easier to visualize at letter scale.

The Result: Gibberish

This has correct letter frequencies but is unreadable. English isn't just about individual letter frequencies—it's about how letters combine. This demonstrates that context matters.

Introducing N-grams

- 1-gram: Individual letter frequencies

- 2-gram: Pairs like "th", "qu", "er"

- 3-gram: Triples like "the", "ing"

In English, P(u|q) ≈ 0.99. This single rule dramatically improves generation!

Scale Jump

Moving from 26 letters to 40,000+ words dramatically increases complexity. Word frequencies follow Zipf's Law: a few words are very common ("the" ~7%), most are rare.

The Combinatorial Explosion

| N-gram | Possible | Observed |

|---|---|---|

| 2-gram | 1.6 billion | ~1 million |

| 3-gram | 60 trillion | ~few million |

| 4-gram | 2.4 quadrillion | ~tens of millions |

Most combinations never occur—we need models that generalize!

What Is a Model?

The Galileo Analogy

Two approaches to knowledge:

- Empirical: Measure every case, store in table

- Theoretical: Find formula that predicts all cases

N-gram counting = measuring each floor

Neural networks = finding the formula

Model = Structure + Parameters

- Structure: Architecture (linear, polynomial, neural net)

- Parameters: Adjustable values (weights, biases)

ChatGPT: Transformer structure + 175 billion parameters

Models for Human-Like Tasks

The Leap to Human Tasks

Physics has equations like F=ma. What's the equation for "this image contains a cat"? There isn't one we can write simply. Human-like tasks require learning patterns from examples.

Neural Nets

Biological Inspiration

- Brain: 100 billion neurons, ~1000 activations/sec

- ChatGPT: 175 billion parameters, billions ops/sec

Modern neural nets are inspired by but not faithful to biology.

output = f(w · x + b) Where: x = input vector w = weights (learned) b = bias (learned) f = activation (e.g., ReLU) ReLU: f(x) = max(0, x)

Machine Learning, and the Training of Neural Nets

Learning = Parameter Adjustment

Network structure is fixed. Learning means finding right weights. For ChatGPT: find 175 billion numbers that make it good at predicting text.

The Landscape Metaphor

- High loss = mountain peak (bad)

- Low loss = valley bottom (good)

- Gradient descent = rolling downhill

With 175B parameters, this "landscape" has 175B dimensions!

The Practice and Lore of Neural Net Training

Art vs. Science

"Lore" = knowledge passed through practice, not theory. Many decisions work empirically but lack theoretical justification. Architecture, hyperparameters, data—all involve craft knowledge.

"Surely a Network That's Big Enough Can Do Anything!"

Fundamental Limits

Some computations can't be shortcut—they require step-by-step execution. No neural network, regardless of size, can bypass computational irreducibility.

The Concept of Embeddings

Words as Vectors

Each word becomes a point in high-dimensional space. Similar meanings → similar vectors. "King" and "queen" are close; "king" and "banana" are far.

Inside ChatGPT

The Scale

175 billion parameters × 2 bytes = 350GB just for weights. Requires multiple high-end GPUs to run. This is the largest publicly-known model of its era.

The Key Innovation

Attention solves long-range dependencies. In "The cat sat on the mat because it was tired," the word "it" needs to attend to "cat"—attention enables this connection across many tokens.

ChatGPT Architecture Summary

The Training of ChatGPT

Training Data Scale

| Source | Volume |

|---|---|

| Web pages | ~1 trillion words |

| Books | ~100 billion words |

| Total | ~300 billion tokens |

Beyond Basic Training

RLHF Process

- Generate multiple responses

- Humans rank them

- Train reward model on preferences

- Use RL to optimize for reward

This makes ChatGPT helpful and safe, not just good at predicting text.

What Really Lets ChatGPT Work?

The Deep Question

If a statistical model produces convincing language, maybe language itself is more statistical than we thought. This is a discovery about language, not just about AI.

Meaning Space and Semantic Laws of Motion

Meaning as Geometry

Reasoning = trajectories through meaning space. Creativity = novel paths. Coherence = smooth, connected paths. Language generation follows "semantic laws of motion."

Semantic Grammar and the Power of Computational Language

Two Languages

- Natural: Ambiguous, contextual, human

- Computational: Precise, formal, executable

Combining both could give the best of both worlds.

So ... What Is ChatGPT Doing, and Why Does It Work?

The Summary

After 15 chapters, it's simple: predict next token, sample, repeat. The magic is in 175 billion parameters capturing patterns from 300 billion training tokens.

Product Requirements Document

Educational product specification based on Wolfram's essay

Executive Summary

Transform Wolfram's comprehensive essay into accessible, multi-format educational resources for diverse audiences—from executives needing strategic understanding to engineers wanting technical depth.

Target Audiences

| Audience | Level | Primary Need | Format |

|---|---|---|---|

| Executives | Beginner | Strategic understanding | 2-page summary |

| Developers | Intermediate | Implementation details | Code examples |

| ML Engineers | Advanced | Technical depth | Full mathematics |

| Students | Progressive | Learning path | Interactive course |

Why This Opening Matters

Wolfram begins by acknowledging genuine surprise—even AI researchers didn't expect language models to work this well. The word "unexpected" is crucial: this wasn't a foregone conclusion but a discovery.

Key Questions Posed