scikit-learn User Guide

Complete illustrated guide to machine learning in Python

Complete Illustrated Analysis

From linear regression to neural networks - the essential ML toolkit explained

Linear Models

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS)

The Objective

OLS minimizes: Σ(yᵢ - ŷᵢ)² = ||y - Xw||²

Closed-Form Solution

w = (XTX)-1XTy

This has a direct solution - no iteration needed! But it can be numerically unstable and doesn't handle multicollinearity well.

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression # Create and fit model model = LinearRegression() model.fit(X_train, y_train) # Get coefficients print(f"Coefficients: {model.coef_}") print(f"Intercept: {model.intercept_}") # Make predictions y_pred = model.predict(X_test)

Ridge Regression (L2 Regularization)

The Ridge Objective

Minimize: ||y - Xw||² + α||w||²

Why Regularization?

- Prevents overfitting: Penalizes large weights

- Handles multicollinearity: Stabilizes solution

- Shrinks coefficients: But never to exactly zero

The α Parameter

α = 0: Ordinary least squares. α → ∞: All weights → 0. Use cross-validation to find optimal α.

Lasso Regression (L1 Regularization)

The Lasso Objective

Minimize: (1/2n)||y - Xw||² + α||w||₁

Feature Selection

Unlike Ridge, Lasso can set coefficients exactly to zero. This is automatic feature selection! Great when you believe only a few features matter.

When to Use Lasso vs Ridge

- Lasso: When you expect sparse solutions (few important features)

- Ridge: When many features contribute small amounts

- Elastic Net: Combines both (best of both worlds)

Logistic Regression

The Logistic Function (Sigmoid)

P(y=1|x) = 1 / (1 + e-wTx)

Why "Regression" for Classification?

It regresses the log-odds: log(P/(1-P)) = wTx. The output is transformed into probabilities via sigmoid.

Multiclass: One-vs-Rest or Softmax

- OvR: Train K binary classifiers

- Multinomial (Softmax): Single model, K outputs

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression # For binary classification clf = LogisticRegression(C=1.0, solver='lbfgs') clf.fit(X_train, y_train) # Predict probabilities probs = clf.predict_proba(X_test) # Predict classes y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

| Model | Regularization | Feature Selection | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| LinearRegression | None | No | Baseline, interpretability |

| Ridge | L2 (||w||²) | No | Multicollinearity, many features |

| Lasso | L1 (||w||₁) | Yes | Sparse solutions, feature selection |

| ElasticNet | L1 + L2 | Yes | Best of both worlds |

| LogisticRegression | L1/L2/ElasticNet | With L1 | Classification |

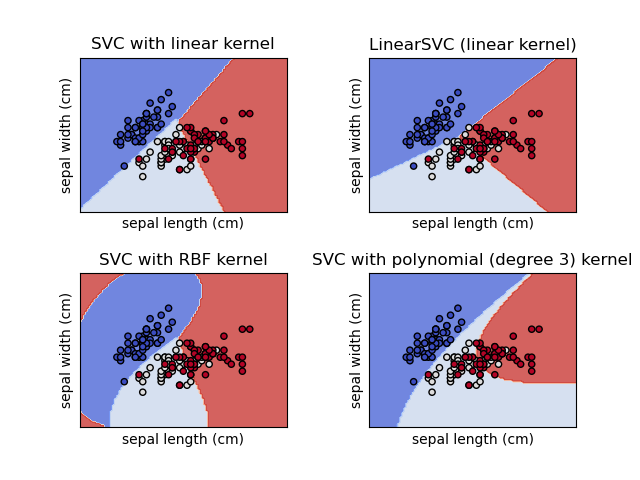

Support Vector Machines

The Core Idea

Find the hyperplane that maximizes the margin between classes. The "support vectors" are the data points closest to this hyperplane - they define the decision boundary.

Why SVMs Excel

- High dimensions: Work well when features > samples

- Kernel trick: Non-linear boundaries without explicit transformation

- Robust: Only support vectors matter, not all data

SVC: Support Vector Classification

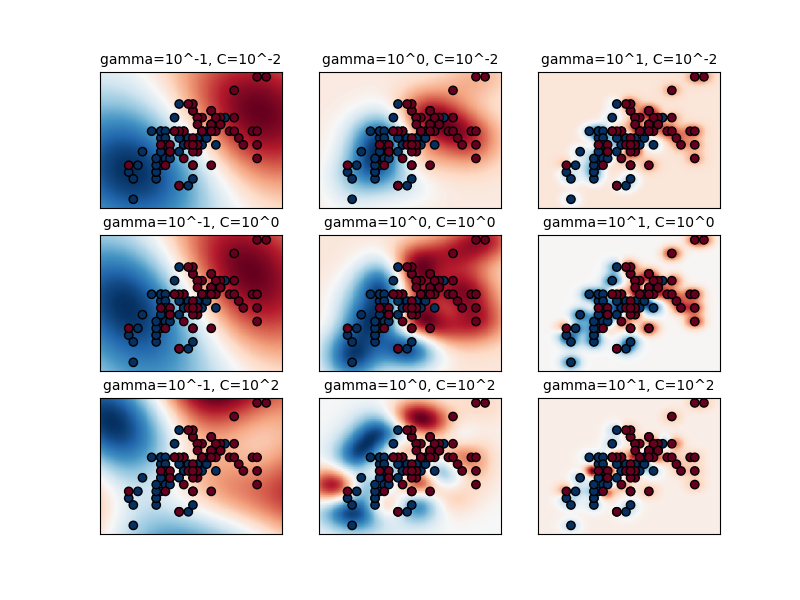

The C Parameter

C controls the trade-off between smooth decision boundary and classifying training points correctly.

- Small C: Smoother boundary, more misclassifications allowed

- Large C: Harder boundary, fewer misclassifications

Scaling Limitation

O(n²) to O(n³) complexity. For >10K samples, consider LinearSVC or SGDClassifier with hinge loss.

from sklearn.svm import SVC from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler # IMPORTANT: Scale your data! scaler = StandardScaler() X_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) # RBF kernel (default) clf = SVC(kernel='rbf', C=1.0, gamma='scale') clf.fit(X_train_scaled, y_train)

Kernel Functions

Common Kernels

- Linear: K(x,y) = xTy - for linearly separable data

- RBF (Gaussian): K(x,y) = exp(-γ||x-y||²) - most versatile

- Polynomial: K(x,y) = (γxTy + r)d

- Sigmoid: K(x,y) = tanh(γxTy + r)

The RBF Gamma Parameter

γ controls how far the influence of a single training example reaches. Low γ = far reach (smoother), high γ = close reach (more complex).

⚠️ Important: Scale Your Data!

SVMs are sensitive to feature scales. Always use StandardScaler or MinMaxScaler before fitting. Without scaling, features with larger values will dominate the kernel computation.

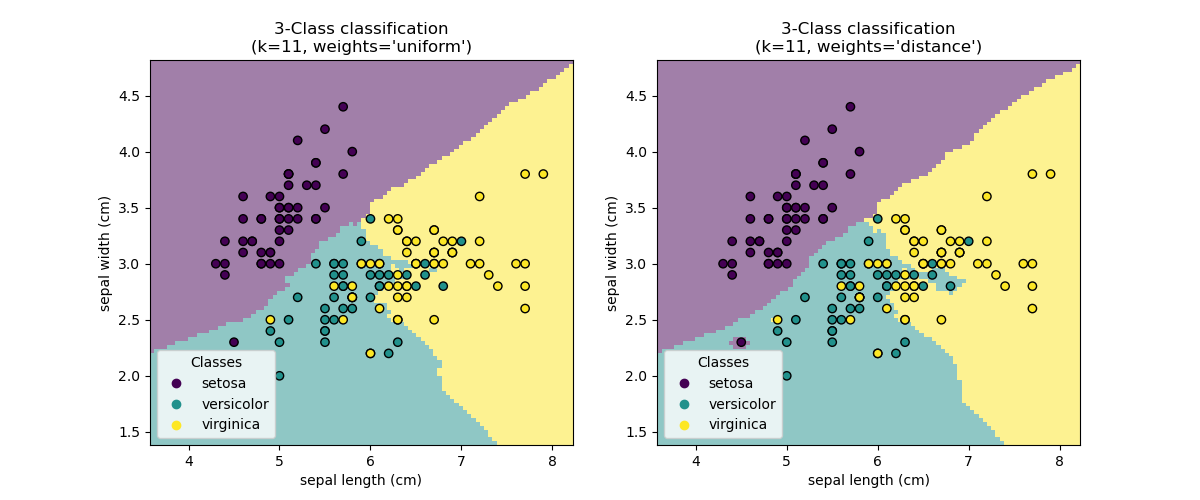

Nearest Neighbors

The Simplest ML Algorithm

KNN is a "lazy learner" - it doesn't build a model, just stores training data. Prediction is: "find k closest points, vote/average their labels."

Advantages

- Simple: No training phase, easy to understand

- Non-parametric: Makes no assumptions about data distribution

- Versatile: Works for classification and regression

Disadvantages

- Slow prediction: Must search all training data

- Memory intensive: Stores all training data

- Curse of dimensionality: Distance becomes meaningless in high dimensions

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier # k=5 is a common default knn = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=5, weights='uniform') knn.fit(X_train, y_train) # Predict y_pred = knn.predict(X_test) # Get probabilities (based on neighbor votes) y_proba = knn.predict_proba(X_test)

KNN Algorithm

- Store all training data

- For a new point x, compute distance to all training points

- Find the k nearest neighbors

- Classification: majority vote of neighbors' labels

- Regression: average (or weighted average) of neighbors' values

When to Use KNN

- Small to medium datasets (< 100K samples)

- Low to medium dimensionality

- When you need a quick baseline

- Recommendation systems (find similar items)

- Anomaly detection (points far from neighbors)

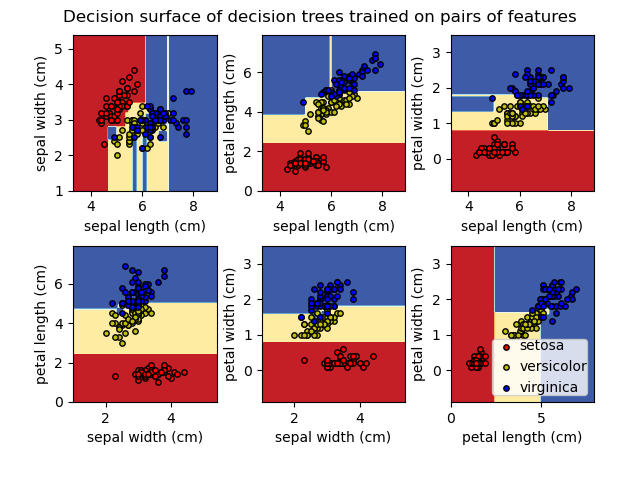

Decision Trees

How Trees Work

A tree recursively splits the data based on feature thresholds. Each internal node is a "question" (e.g., "is feature X > 5?"). Leaves contain predictions.

Key Advantages

- Interpretable: You can visualize and explain the logic

- No scaling needed: Works with raw features

- Handles mixed types: Numerical and categorical

- Feature importance: Built-in feature ranking

Key Disadvantages

- Overfitting: Deep trees memorize training data

- Instability: Small data changes → different trees

- Axis-aligned: Can't capture diagonal boundaries easily

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier, plot_tree import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Create tree with max_depth to prevent overfitting tree = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=3, random_state=42) tree.fit(X_train, y_train) # Visualize the tree plt.figure(figsize=(20, 10)) plot_tree(tree, feature_names=feature_names, class_names=class_names, filled=True) plt.show() # Feature importances print(tree.feature_importances_)

Splitting Criteria

Gini Impurity

Gini = 1 - Σpᵢ² where pᵢ is the probability of class i. Gini = 0 means pure node (all same class).

Entropy

Entropy = -Σpᵢ log(pᵢ). Information gain = parent entropy - weighted child entropy.

In Practice

Gini and entropy usually give similar results. Gini is slightly faster (no log computation).

| Parameter | Purpose | Effect on Overfitting |

|---|---|---|

| max_depth | Maximum tree depth | Lower = less overfitting |

| min_samples_split | Min samples to split a node | Higher = less overfitting |

| min_samples_leaf | Min samples in a leaf | Higher = less overfitting |

| max_features | Features to consider for split | Lower = less overfitting |

| ccp_alpha | Cost-complexity pruning | Higher = more pruning |

Ensemble Methods

Why Ensembles Work

Different models make different errors. By combining them, errors can cancel out. "Wisdom of the crowd" - many weak learners → one strong learner.

Two Main Strategies

- Bagging: Train models independently in parallel, average results (reduces variance)

- Boosting: Train models sequentially, each fixing previous errors (reduces bias)

Random Forest

How Random Forest Works

- Create N bootstrap samples (random sampling with replacement)

- For each sample, train a decision tree

- At each split, consider only √features (random feature subset)

- Aggregate predictions: majority vote (classification) or average (regression)

Why It Works

Bootstrap + random features → decorrelated trees → reduced variance. Individual trees may overfit, but their errors are different and cancel out!

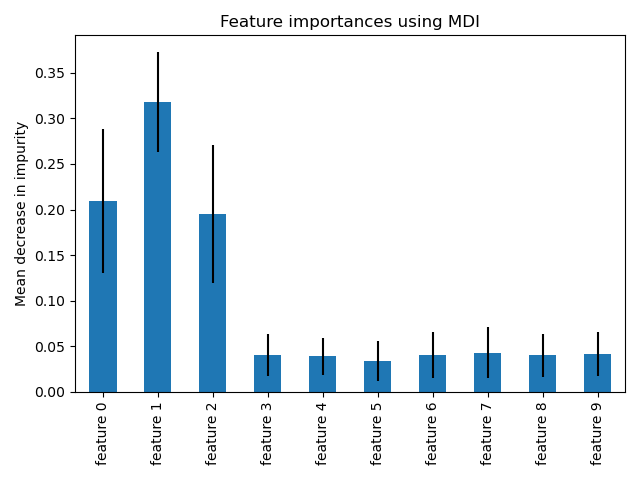

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier # Create forest with 100 trees rf = RandomForestClassifier( n_estimators=100, # number of trees max_depth=None, # let trees grow fully min_samples_split=2, max_features='sqrt', # √features at each split n_jobs=-1, # use all CPU cores random_state=42 ) rf.fit(X_train, y_train) # Feature importances (averaged across all trees) importances = rf.feature_importances_

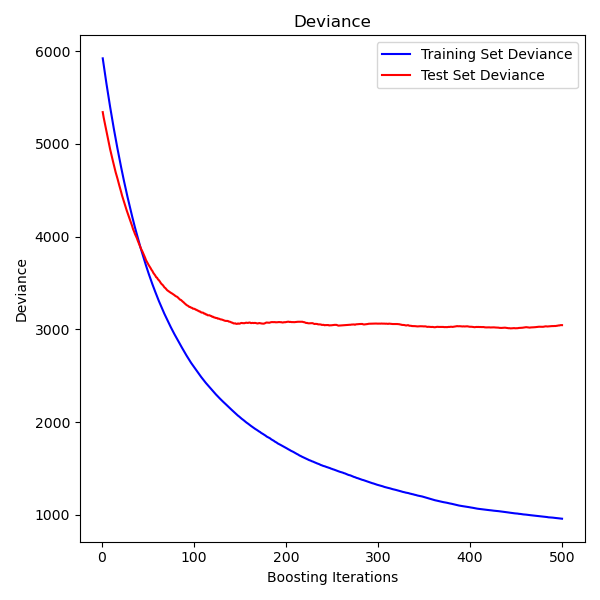

Gradient Boosting

How Gradient Boosting Works

- Start with a simple prediction (e.g., mean)

- Compute residuals (errors)

- Fit a tree to predict the residuals

- Add tree's predictions (scaled by learning rate) to model

- Repeat: fit new trees to new residuals

Key Parameters

- n_estimators: Number of boosting stages

- learning_rate: Shrinks each tree's contribution (lower = more trees needed)

- max_depth: Usually shallow (3-10) for boosting

| Method | Strategy | Trees | Speed | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RandomForest | Bagging | Parallel, deep | Fast (parallel) | General purpose, feature importance |

| GradientBoosting | Boosting | Sequential, shallow | Slower | High accuracy, tuned models |

| HistGradientBoosting | Boosting | Sequential, histogram | Very fast | Large datasets, native NaN handling |

| AdaBoost | Boosting | Sequential, stumps | Fast | Simple boosting baseline |

Neural Network Models

When to Use sklearn's Neural Networks

sklearn's MLP is ideal for tabular data where you want neural network benefits without deep learning complexity. It follows the standard fit/predict API, integrates with cross-validation and pipelines, and requires no GPU setup.

Limitations to Consider

- No GPU support: CPU-only, slower for large networks

- Limited architectures: Only fully-connected layers

- No custom layers: Can't build CNNs, RNNs, or transformers

from sklearn.neural_network import MLPClassifier from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline # Neural networks REQUIRE scaling! clf = make_pipeline( StandardScaler(), MLPClassifier( hidden_layer_sizes=(100, 50), # 2 hidden layers activation='relu', # ReLU activation solver='adam', # Adam optimizer max_iter=500, early_stopping=True, # Prevent overfitting random_state=42 ) ) clf.fit(X_train, y_train) print(f"Accuracy: {clf.score(X_test, y_test):.3f}")

Choosing Architecture Size

- Start small: (100,) often works well

- Add depth: (100, 50) for more complex patterns

- Rule of thumb: Total neurons < training samples

Solver Selection

- adam: Default, works well for most cases

- lbfgs: Better for small datasets (<10k samples)

- sgd: More control, requires tuning learning rate

| Parameter | Options | Default | When to Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| hidden_layer_sizes | tuple of ints | (100,) | Complex data needs more layers |

| activation | relu, tanh, logistic | relu | Rarely - relu works well |

| solver | adam, sgd, lbfgs | adam | lbfgs for small data |

| alpha | float | 0.0001 | Increase for regularization |

| learning_rate_init | float | 0.001 | Lower if not converging |

| early_stopping | bool | False | True to prevent overfitting |

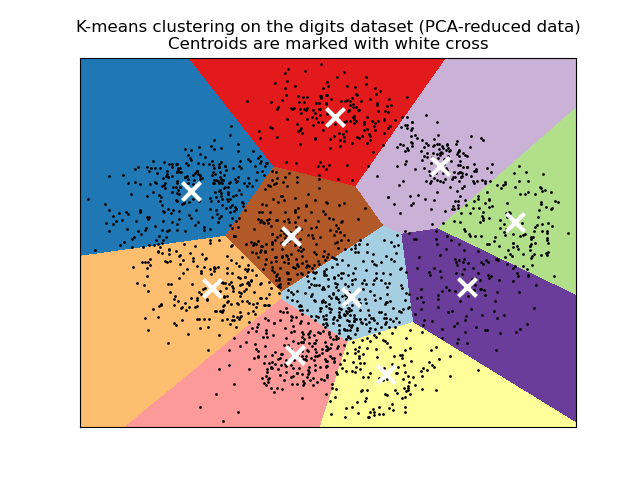

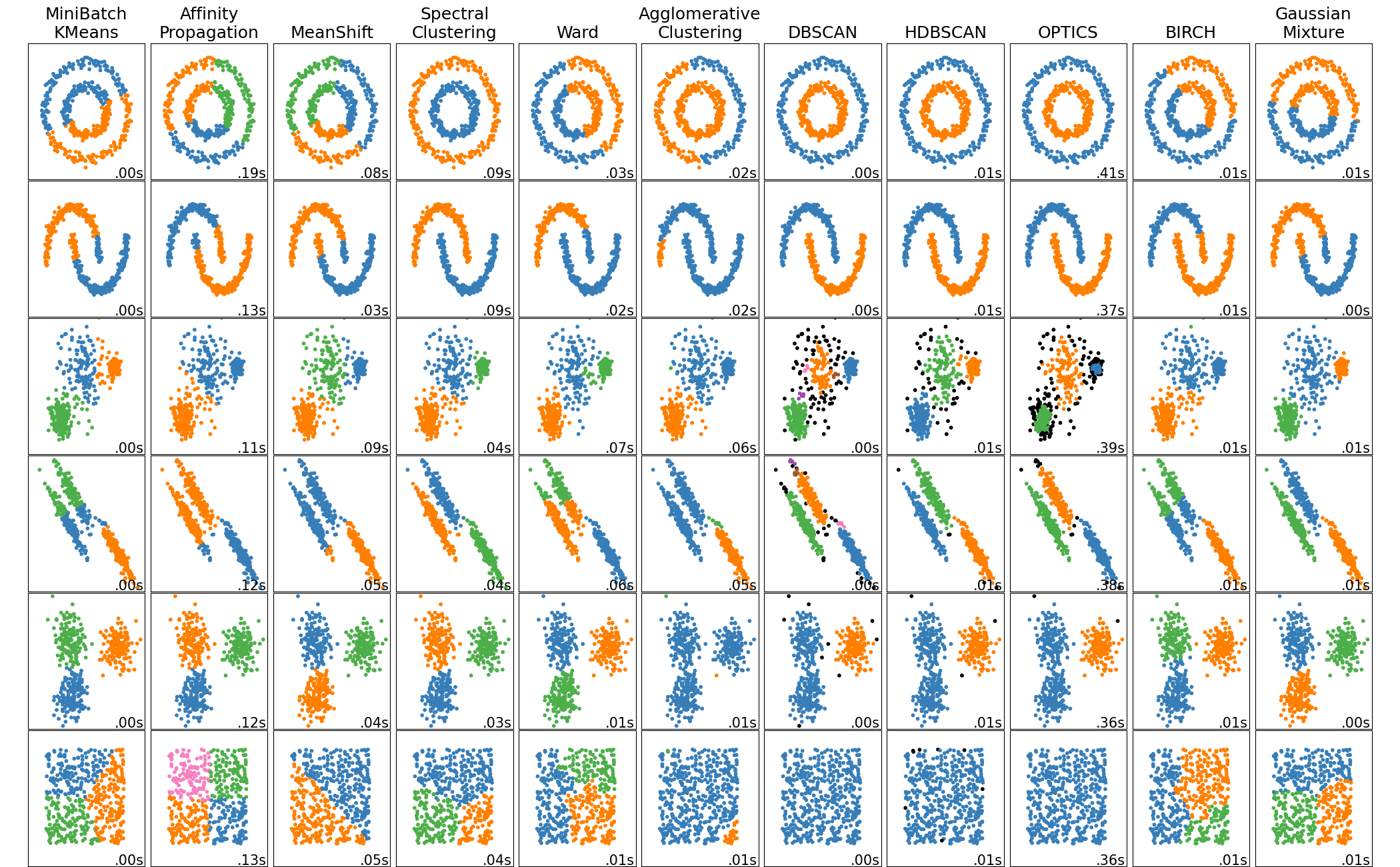

Clustering: Unsupervised Grouping

The Unsupervised Learning Paradigm

Without labels, clustering algorithms use different criteria to define "good" clusters: minimizing within-cluster variance (KMeans), maximizing density (DBSCAN), or building hierarchies (AgglomerativeClustering). The right choice depends on your data's shape and your goals.

Real-World Applications

- Customer segmentation: Group users by behavior

- Anomaly detection: Points far from clusters are outliers

- Data compression: Replace points with cluster centers

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler # Scale features (important for distance-based methods) X_scaled = StandardScaler().fit_transform(X) # Fit KMeans with 5 clusters kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=5, random_state=42, n_init=10) labels = kmeans.fit_predict(X_scaled) # Cluster centers and inertia centers = kmeans.cluster_centers_ inertia = kmeans.inertia_ # Sum of squared distances to centers

Choosing the Right Algorithm

- KMeans: Fast, spherical clusters, need to know K

- DBSCAN: Arbitrary shapes, handles outliers, no K needed

- Agglomerative: Hierarchical view, works with any linkage

- MiniBatchKMeans: Very large datasets

The K Selection Problem

For KMeans, use the elbow method (plot inertia vs K) or silhouette scores. DBSCAN avoids this but requires tuning eps (neighborhood radius) and min_samples.

from sklearn.cluster import DBSCAN # eps: max distance between neighbors # min_samples: minimum points to form a cluster dbscan = DBSCAN(eps=0.5, min_samples=5) labels = dbscan.fit_predict(X_scaled) # -1 labels indicate noise/outliers n_clusters = len(set(labels)) - (1 if -1 in labels else 0) n_outliers = list(labels).count(-1) print(f"Found {n_clusters} clusters, {n_outliers} outliers")

| Algorithm | Cluster Shape | Scalability | Requires K? | Handles Outliers? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMeans | Spherical | O(n) | Yes | No |

| MiniBatchKMeans | Spherical | Very fast | Yes | No |

| DBSCAN | Arbitrary | O(n²) or O(n log n) | No | Yes |

| AgglomerativeClustering | Depends on linkage | O(n²) | Yes | No |

| HDBSCAN | Arbitrary | O(n log n) | No | Yes |

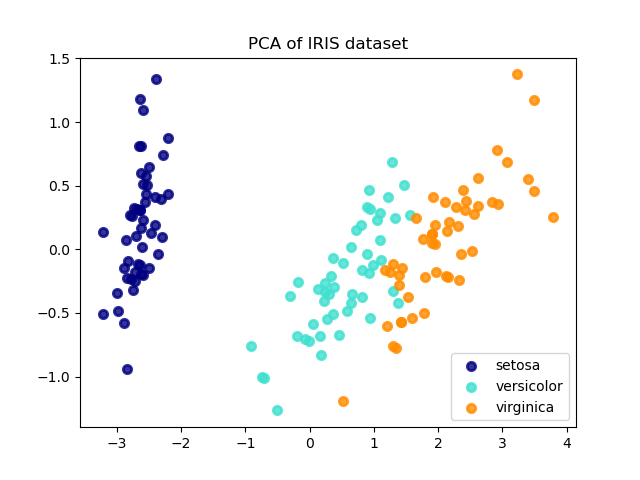

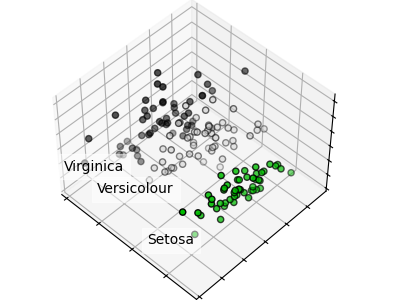

Dimensionality Reduction

Why Reduce Dimensions?

- Curse of dimensionality: Many algorithms degrade with high dimensions

- Visualization: Project to 2D/3D for human understanding

- Noise reduction: Remove low-variance (noisy) components

- Speed: Faster training with fewer features

PCA Intuition

PCA finds new axes (principal components) aligned with the directions of maximum variance. The first component captures the most variance, the second captures the most remaining variance orthogonal to the first, and so on.

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler # Always standardize before PCA scaler = StandardScaler() X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X) # Keep components explaining 95% variance pca = PCA(n_components=0.95) X_reduced = pca.fit_transform(X_scaled) print(f"Reduced: {X.shape[1]} → {X_reduced.shape[1]} features") print(f"Variance explained: {pca.explained_variance_ratio_.sum():.1%}")

Choosing the Right Method

- PCA: General purpose, linear, unsupervised

- TruncatedSVD: Sparse data (text, counts)

- LDA: When you have labels and want class separation

- t-SNE: Visualization only (slow, non-deterministic)

How Many Components?

Use n_components=0.95 to keep 95% variance, or plot cumulative explained variance ratio to find the "elbow". For visualization, use n_components=2 or 3.

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline from sklearn.decomposition import PCA from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression # PCA as preprocessing in a pipeline pipe = Pipeline([ ('scaler', StandardScaler()), ('pca', PCA(n_components=50)), ('clf', LogisticRegression()) ]) # Tune n_components with GridSearchCV from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV param_grid = {'pca__n_components': [10, 30, 50, 100]} search = GridSearchCV(pipe, param_grid, cv=5) search.fit(X_train, y_train)

| Method | Type | Supervised? | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | No | General preprocessing, variance preservation |

| TruncatedSVD | Linear | No | Sparse matrices, text data (LSA) |

| LDA | Linear | Yes | Classification preprocessing |

| t-SNE | Nonlinear | No | Visualization only |

| UMAP | Nonlinear | No | Visualization, faster than t-SNE |

| NMF | Linear | No | Non-negative data (images, text) |

Cross-Validation and Model Selection

Why Cross-Validation Matters

A single train/test split can be lucky or unlucky. Cross-validation averages over multiple splits, giving you both a mean score and standard deviation. This helps detect if your model's performance varies wildly across different data subsets.

Common CV Strategies

- KFold: Standard K splits, default K=5

- StratifiedKFold: Preserves class proportions (classification)

- LeaveOneOut: K = n, expensive but unbiased

- TimeSeriesSplit: Respects temporal order

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score, cross_validate from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier clf = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100) # Simple: Get array of scores scores = cross_val_score(clf, X, y, cv=5, scoring='accuracy') print(f"Accuracy: {scores.mean():.3f} (+/- {scores.std()*2:.3f})") # Detailed: Multiple metrics, timing results = cross_validate(clf, X, y, cv=5, scoring=['accuracy', 'f1_macro'], return_train_score=True ) print(results['test_accuracy']) print(results['fit_time'])

Grid vs Random Search

- GridSearchCV: Tests all combinations. Good for small grids.

- RandomizedSearchCV: Samples n_iter combinations. Better for large spaces.

- Research shows: 60 random iterations often beats exhaustive grid search

Avoiding Data Leakage

Always put preprocessing inside the cross-validation loop. Use Pipeline to ensure scaling/encoding is fit only on training folds, not the entire dataset.

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline from sklearn.svm import SVC # Pipeline ensures no data leakage pipe = Pipeline([ ('scaler', StandardScaler()), ('svc', SVC()) ]) # Parameter grid (use double underscore for nested params) param_grid = { 'svc__C': [0.1, 1, 10, 100], 'svc__kernel': ['rbf', 'linear'], 'svc__gamma': ['scale', 'auto', 0.1, 0.01] } search = GridSearchCV(pipe, param_grid, cv=5, scoring='f1_macro', n_jobs=-1) search.fit(X_train, y_train) print(f"Best params: {search.best_params_}") print(f"Best CV score: {search.best_score_:.3f}") print(f"Test score: {search.score(X_test, y_test):.3f}")

| Scorer | Task | Best When |

|---|---|---|

| accuracy | Classification | Balanced classes |

| f1, f1_macro, f1_weighted | Classification | Imbalanced classes |

| roc_auc | Binary classification | Ranking quality matters |

| neg_mean_squared_error | Regression | General regression |

| r2 | Regression | Variance explained |

| neg_log_loss | Classification | Probability calibration matters |

Data Preprocessing

Why Preprocessing Matters

- Scaling: Many algorithms (SVM, KNN, neural nets) are sensitive to feature scales

- Encoding: ML models need numeric inputs, not strings

- Missing values: Most algorithms can't handle NaN

Fit vs Transform

Fit learns parameters from training data (mean, std, categories). Transform applies those parameters. Always fit on training data only, then transform both train and test to avoid data leakage.

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler, RobustScaler # StandardScaler: zero mean, unit variance (most common) scaler = StandardScaler() X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X_train) X_test_scaled = scaler.transform(X_test) # Use train params! # MinMaxScaler: scale to [0, 1] range scaler = MinMaxScaler() # RobustScaler: use median/IQR, robust to outliers scaler = RobustScaler()

Encoding Strategy

- Ordinal: Education level (high school < bachelor < master)

- One-Hot: Colors, countries, product categories

- Target encoding: High-cardinality categories (use category_encoders library)

Common Pitfall

Don't use OneHot for high-cardinality features (1000+ categories). This creates sparse matrices and can cause overfitting. Consider target encoding or hashing instead.

from sklearn.preprocessing import OneHotEncoder, StandardScaler from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline # Define column groups numeric_features = ['age', 'income', 'score'] categorical_features = ['gender', 'city', 'category'] # Create preprocessing pipelines for each type numeric_transformer = Pipeline([ ('imputer', SimpleImputer(strategy='median')), ('scaler', StandardScaler()) ]) categorical_transformer = Pipeline([ ('imputer', SimpleImputer(strategy='constant', fill_value='missing')), ('onehot', OneHotEncoder(handle_unknown='ignore')) ]) # Combine with ColumnTransformer preprocessor = ColumnTransformer([ ('num', numeric_transformer, numeric_features), ('cat', categorical_transformer, categorical_features) ])

| Scaler | Formula | Use When |

|---|---|---|

| StandardScaler | (x - mean) / std | Default choice, assumes Gaussian |

| MinMaxScaler | (x - min) / (max - min) | Bounded features, neural networks |

| RobustScaler | (x - median) / IQR | Data has outliers |

| MaxAbsScaler | x / max(|x|) | Sparse data, preserves zeros |

| Normalizer | x / ||x|| | Per-sample L2 normalization (text) |

Pipelines and Composite Estimators

Why Pipelines Are Essential

- No data leakage: Fit only sees training fold in CV

- Clean code: One object does fit → transform → predict

- Reproducible: Same pipeline produces same results

- Deployable: Pickle the pipeline, deploy anywhere

Pipeline Behavior

When you call pipeline.fit(X, y), it calls fit_transform on all transformers in sequence, then fit on the final estimator. predict() calls transform on all transformers, then predict on the final estimator.

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler, OneHotEncoder from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV # Feature groups num_cols = ['age', 'balance'] cat_cols = ['job', 'education'] # Preprocessor preprocessor = ColumnTransformer([ ('num', Pipeline([ ('impute', SimpleImputer(strategy='median')), ('scale', StandardScaler()) ]), num_cols), ('cat', Pipeline([ ('impute', SimpleImputer(strategy='most_frequent')), ('encode', OneHotEncoder(handle_unknown='ignore')) ]), cat_cols) ]) # Full pipeline pipe = Pipeline([ ('preprocess', preprocessor), ('classifier', RandomForestClassifier()) ]) # GridSearch with nested parameter names param_grid = { 'classifier__n_estimators': [100, 200], 'classifier__max_depth': [10, 20, None] } search = GridSearchCV(pipe, param_grid, cv=5, n_jobs=-1) search.fit(X_train, y_train) print(f"Best score: {search.best_score_:.3f}")

Pipeline vs FeatureUnion

- Pipeline: Sequential (A → B → C), output of A is input to B

- FeatureUnion: Parallel, same input to A, B, C; outputs concatenated

- ColumnTransformer: Different columns to different transformers

make_pipeline Shortcut

Use make_pipeline(StandardScaler(), PCA(50), LogisticRegression()) for quick pipelines. Step names are auto-generated from class names (lowercase).

import joblib # Save the fitted pipeline joblib.dump(pipe, 'model_pipeline.pkl') # Load for inference loaded_pipe = joblib.load('model_pipeline.pkl') predictions = loaded_pipe.predict(new_data) # The loaded pipeline includes ALL preprocessing # Just pass raw data - it handles everything

Glossary

Key terms and concepts in scikit-learn

Quick Reference Cheat Sheet

Common patterns and best practices

The Universal API Pattern

from sklearn.module import ModelClass # 1. Instantiate model = ModelClass(hyperparameters) # 2. Fit model.fit(X_train, y_train) # 3. Predict y_pred = model.predict(X_test) # 4. Evaluate score = model.score(X_test, y_test)

Common Workflow

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split, cross_val_score from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier # Split data X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split( X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42 ) # Create pipeline pipe = Pipeline([ ('scaler', StandardScaler()), ('clf', RandomForestClassifier()) ]) # Cross-validation scores = cross_val_score(pipe, X_train, y_train, cv=5) print(f"CV Score: {scores.mean():.3f} (+/- {scores.std():.3f})") # Final fit and evaluation pipe.fit(X_train, y_train) print(f"Test Score: {pipe.score(X_test, y_test):.3f}")

Why Start with Linear Models?

Linear models are interpretable, fast, and often surprisingly effective. They form the basis for understanding more complex models. Even neural networks are stacks of linear transformations with non-linear activations.

Key Advantages